Tom Brady is one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time.

He is not the greatest.

You probably already have your mouse hovering over the “X,” thinking this is a biased argument from a bitter New York Jets fan. That is not the case. Believe me, this article praises numerous figures who are not popular in the land of Jets football.

This is merely a delivery of the facts – specifically, facts that most fans and analysts are either unaware of or choose to ignore. All logic seems to fly out the window whenever this player’s legacy is discussed. Brady’s aura has grown to overshadow his actual production, and I believe it is time to set the record straight. Consider this an act of public service.

Come along for the ride with me, as we peruse the cold, hard evidence that proves Tom Brady is not, in fact, the “GOAT”.

What does it even mean to be the “GOAT”?

Team accomplishments are not a factor

Everyone has different definitions for this term, but in my mind, the “greatness” in question refers to individual greatness. That means team accomplishments should be out of the discussion.

While the whole purpose of individual success is to facilitate team success, that does not mean the two things are always directly correlated. If they were, it would mean Robert Horry is a better player than Michael Jordan, or that LeGarrette Blount is better than Dan Marino.

Rings are especially less important when talking about football’s GOAT debate. In basketball, an individual player has much greater control over his team’s success than in football. It’s simple math: There are 10 players on a basketball court and 22 on a football field. Each individual basketball player makes up 10% of the people on the court, more than twice as high as each individual football player (4.5%).

Plus, while basketball players could play up to 90% or even 100% of the available minutes in a given playoff game (which entails playing both sides of the court), most football players (and all quarterbacks) will play a maximum of about 50% of the available snaps, since they only play one phase of the game. That number drops to around 40% if we include special teams.

Here’s an example. In the 1993 NBA Finals, Michael Jordan played 274 of 303 possible minutes: 91%. In Super Bowl LV, Tom Brady participated in 69 of the game’s 179 total snaps: 39%.

Let’s take it one step further by accounting for the number of players on the court/field.

In the 1993 NBA Finals, Jordan accounted for 274 of the 3,030 available minutes among all players: 9%. In Super Bowl LV, Brady accounted for 69 of the 3,938 snaps among all players: 1.8%.

Why should we judge players by their team’s success when they are responsible for less than 10% of the action in a given game? This applies to both sports, but it is especially true for a quarterback, who accounts for less than 2% of the reps taken in a game.

Yes, it is obvious that a basketball team’s star player or a football team’s quarterback carries more importance than any other player in the game; all minutes and snaps should not be weighed equally.

But even if we double, triple, or quadruple those percentages to account for the difference in value, the individual player’s role in the final outcome would still be much too small for us to deem them responsible for the team’s success. One player will always have a substantially smaller effect on the final outcome than the rest of the players combined, no matter how important that player is.

For these reasons, team success will be omitted from this analysis. I think team success can be slightly considered in the NBA’s GOAT debate; as shown by the numbers above, basketball players certainly have a much larger impact on team success than football players. However, I think it is blatantly obvious that team success should have no role in the NFL’s version.

Efficiency over volume

Brady is No. 1 all-time in numerous counting stats, both in the regular season and in the playoffs. This is bound to happen, as he’s played the most games and thrown the most passes (his advantage in the playoffs is particularly massive). LeBron James has made more three-pointers than Kyle Korver; it does not mean he is a better three-point shooter.

In my opinion, efficiency should outweigh volume in the GOAT debate. Some might value longevity and cumulative production in this conversation, and if you do, that is completely fair. I understand that perspective.

Personally, though, I think longevity is a separate skill from what entails “greatness.” I want to find the player who was the most dominant on a per-play basis over the duration of his career, regardless of how many games or pass attempts were included in that career. You shouldn’t be rewarded for racking up more opportunities to accumulate totals if you weren’t as effective with those extra opportunities.

Do other positions count?

The unique challenge with football’s GOAT debate is that it can be difficult to compare players across positions. Each position’s value is subjective.

Basketball is essentially a positionless sport, making it easier to compare any two players even if their roles are different. In baseball and hockey, there are catch-all metrics like WAR and point shares that can be used to compare the value of players across completely different positions. Football does not have metrics of that sort.

Some contend that the NFL’s GOAT is Jerry Rice, who arguably stands out more among wide receivers than any other player compared to their position. The debate, then, is whether that makes Rice more impactful (or “greater”) than the best quarterback.

I can see both sides of that argument, but for the sake of this article, we are just going to stick with quarterbacks. Since quarterbacks are widely viewed as the most important position on the field, it stands to reason that the most impactful player in the sport’s history is probably a quarterback, even if there may be players at other positions who were more impressive relative to their peers.

Era adjustments

When comparing players across eras in any sport, it is essential to account for changes in the league averages. Whether it’s the NBA’s uptick in pace and three-point attempts or the NFL’s uptick in passing volume and passing efficiency, players need to be compared based on how they fared relative to their own eras.

Joe Montana led the NFL with a completion percentage of 61.3% in 1985. In 2024, that would have ranked 32nd in the league (out of 36 qualifiers), slotting between Caleb Williams and Jameis Winston. We cannot compare Montana’s numbers against Brady’s without accounting for the fact that Montana played in an era that was much less conducive to passing efficiency.

Everything we look at in this article will be era-adjusted. It allows us to evaluate any two players on an even plane.

To summarize, here are the four factors to keep in mind:

- Team success is a non-factor

- Efficiency > Volume

- QBs only

- Era-adjusted

It’s time to uncover the truth: Tom Brady is not the GOAT.

Career efficiency adjusted for era

First and foremost, it is abundantly clear that Brady’s career efficiency is not in the conversation to be the greatest of all time.

We will compare Brady to his competitors using era-adjusted career metrics, starting with passer rating.

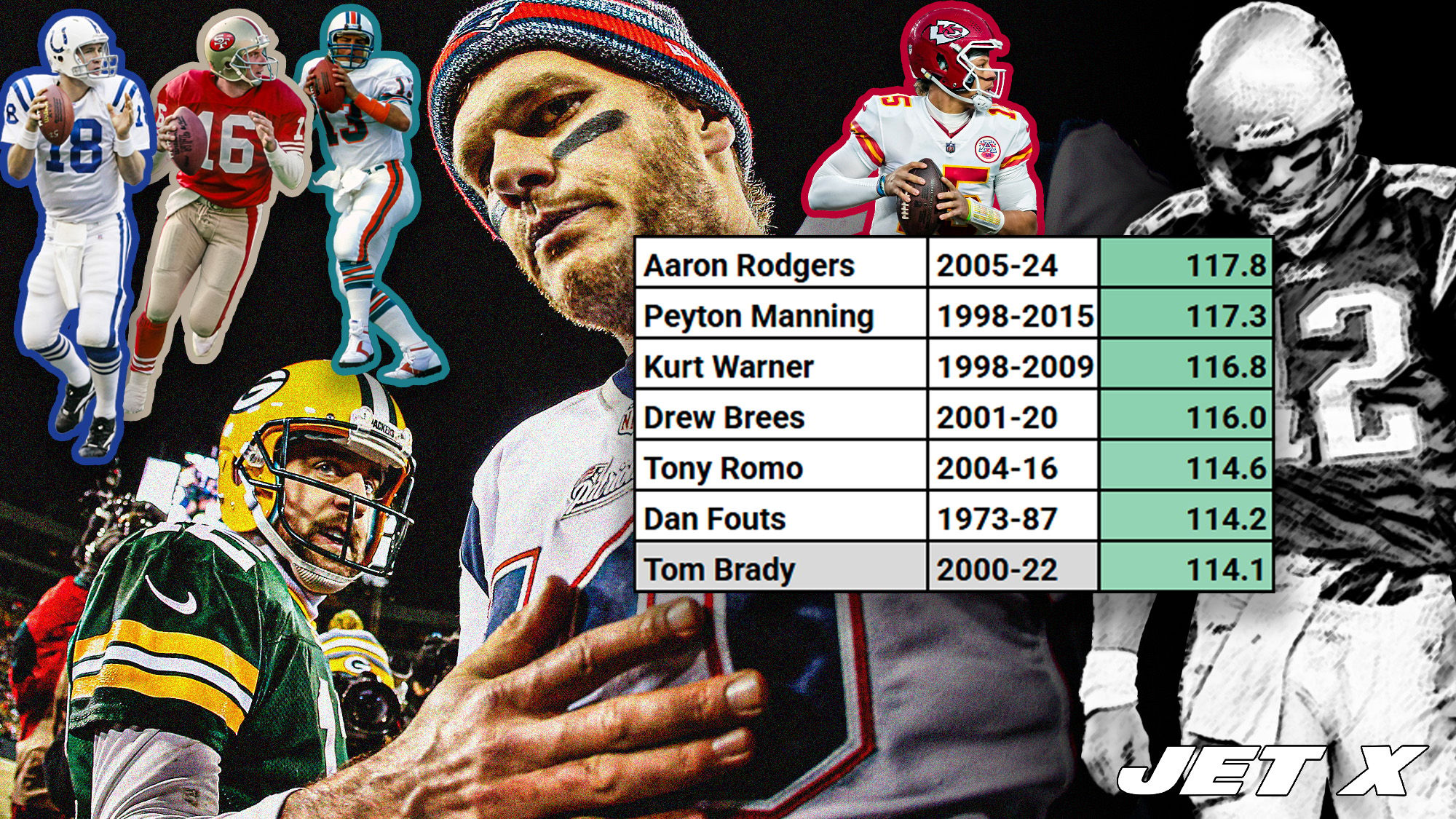

Brady’s career passer rating was 97.2. Over the era he played in (2000-22), the league average passer rating was 85.2. His rating was 114.1% of the NFL average, giving him a 114.1 era-adjusted passer rating (with 100.0 equating a league-average rating in any era).

This number is one of the best in league history, but it is not close to the No. 1 spot. Many legendary quarterbacks have a comfortable advantage.

Among quarterbacks who debuted after the 1970 merger, here are the all-time leaders in net passer rating among quarterbacks with at least 3,000 career pass attempts.

Brady lands in the 10th slot. He is only marginally behind Dan Fouts and Tony Romo, but he is comfortably behind Drew Brees, Kurt Warner, Peyton Manning, Aaron Rodgers, Ken Anderson, Joe Montana, and Steve Young.

The outcome is similar if we use other metrics.

Another valuable catch-all metric for quarterback play is “adjusted net yards per attempt,” or ANY/A. It accounts for yards per pass attempt, touchdowns, interceptions, sacks, and sack yardage to provide a more all-encompassing measure of a quarterback’s ability to move the ball down the field than standard yards per attempt.

Here are the top 15 quarterbacks in era-adjusted ANY/A.

Brady falls one spot to 11th. While Romo drops behind him, Mahomes and Marino jump ahead, the latter with a significant advantage.

Now, let’s bring these two metrics together. Here are the top 25 quarterbacks based on the combined average of their era-adjusted passer rating and era-adjusted ANY/A.

Brady sits in the 10th spot. He is nearly identical to Romo and Mahomes. Eight quarterbacks are at least two points ahead, and seven have him beat in both metrics.

How can one be considered the greatest quarterback of all time if he is not even close to having the all-time best era-adjusted passing efficiency?

Subpar performance in playoffs

Okay, sure, Brady’s regular season efficiency isn’t quite the greatest of all time. But this is a guy with seven championship rings. You are probably thinking, “It’s Brady’s performance in the playoffs that puts him over the top.”

Not so fast.

Despite his reputation as a clutch performer who always steps up in the biggest moments, Brady actually played worse in the playoffs.

While that is not unusual for a quarterback (considering the jump in competition and the decline in temperatures), the harsh truth is that Brady experienced a larger decline in the playoffs than many of his all-time-great peers. It is a damning indictment on his supposed reputation as a “winner.”

Let’s take the top 12 quarterbacks from the combined era-adjusted leaderboard that we analyzed just a few paragraphs ago. These are Brady’s closest competitors in the all-time debate (there is a big drop-off after the No. 12 spot on that list). How does he compare to them in terms of rising to the occasion in the playoffs? Surely, the seven-time champ will separate himself in this category.

Here is how they stack up according to the difference in their playoff numbers versus their regular season numbers.

Brady ranked eighth of 12 with a -7.4 passer rating differential, more than five points below the group average (-2.3). He placed seventh with a -0.62 ANY/A differential, about one-third of a yard below the group average (-0.28).

How did this man win seven rings? (Oh, don’t worry, we’ll get to that.)

No, I am not suggesting that Brady’s playoff dip was far out of the ordinary. Manning, Marino, Fouts, Romo, and Young all fared even worse. The point is not that Brady was “bad” in the playoffs.

He was just… fine.

“GOATs” aren’t “fine” on their sport’s biggest stage.

It is a fact that Brady was nowhere close to “great” in the playoffs, which is something you would expect to see from someone commonly labeled the “Greatest Of All Time.” Brees, Montana, Mahomes, Warner, Anderson, and even the supposed “playoff choker” Aaron Rodgers all performed much better in the playoffs than Brady.

Yet, since Brady is the one with seven rings, he is the guy who people view as the all-time great playoff performer.

It is one of the NFL’s most prominent examples of the Mandela Effect. Just because Brady participated in a lot of wins and stockpiled counting stats over an unprecedented number of games, people have progressively forgotten that he was an average quarterback in the playoffs. Blinded by nostalgia, the world has developed a misguided image of Brady as a stone-cold assassin who stepped up to lead his team to all of those rings.

It is shocking how often we forget there are 22 players on the field.

Brady is the luckiest playoff quarterback in history. Consider this: Brady had 15 playoff games where he posted a passer rating below 75 (which would be below the NFL average in all 23 of his seasons). That’s nearly one-third of his 48 playoff games. His record in those games? 8-7 (.533).

That is not supposed to happen. Since 2000, NFL teams without Brady are 37-121 (.234) when posting a sub-75 passer rating in the playoffs.

To Brady’s credit, he was excellent in the Super Bowl. In 10 trips, he completed 65.8% of his passes for 3,039 yards, 21 touchdowns, and six interceptions. He posted a 97.7 passer rating and 6.97 ANY/A, numbers that are nearly identical to his career regular season averages (97.2, 7.02). That’s fantastic.

However, Brady is lucky to have reached that many Super Bowls based on his poor performance in conference championship games. In 14 trips to the championship round, Brady generated an 82.7 passer rating (-15.0 versus regular season career) and 5.89 ANY/A (-1.13 versus regular season career). Yet, he went 10-4 in those games, which is extremely incongruent with his individual production.

Brady posted a sub-80 passer rating in eight of his 14 conference championship games. By some inexplicable stroke of luck, he went 5-3 in those games. The rest of the NFL is 7-25 (.219) when posting a sub-80 passer rating in the conference championship since 2000.

Without one of the strongest juggernauts in NFL history around him, Brady would not have done nearly as much winning in the playoffs. Time and time again, he came up small, but was bailed out by a loaded Patriots team.

Compare Brady to one of his primary rivals in the GOAT debate, Patrick Mahomes, who has contributed to his team’s championships with a congruent level of production.

Among players with at least 200 playoff pass attempts since 1970, Mahomes has the highest playoff passer rating in NFL history at 105.4, which is more than three points above his regular season average. Mahomes raises his game when the stakes are higher and the opponents are tougher. He deserves his rings.

Meanwhile, Brady’s 89.8 playoff passer rating is just 16th among the 59 quarterbacks with at least 200 playoff pass attempts since 1970.

- Patrick Mahomes (105.4)

- Kurt Warner (102.8)

- Matthew Stafford (102.3)

- Josh Allen (101.7)

- Matt Ryan (100.8)

- Aaron Rodgers (100.1)

- Nick Foles (98.8)

- Alex Smith (97.4)

- Drew Brees (97.1)

- Russell Wilson (96.8)

- Joe Montana (95.6)

- Jalen Hurts (95.4)

- Joe Burrow (93.8)

- Dak Prescott (91.8)

- Joe Theismann (91.4)

- Tom Brady (89.8)

- Troy Aikman (88.3)

- Joe Flacco (87.9)

- Cam Newton (87.7)

- Eli Manning (87.4)

This list highlights how ridiculous it is to extol Brady as some sort of untouchable playoff god who descended from the gridiron heavens to bless us with his clutch gene. He was pretty good, sure. But he was an outlier of epic proportions to win as many rings as he did.

For instance, Aaron Rodgers is often chastised for his lack of playoff success. It is used as the primary argument for why Brady was the better player.

Rodgers was excellent in the playoffs, though. Contrary to Brady, who racked up wins when he played poorly, Rodgers lost many playoff games when he played tremendously.

Rodgers owns an NFL-record seven playoff losses in which he posted a 90+ passer rating. His teams went 10-7 when he posted a 90+ passer rating in the playoffs. Compare that to Brady, whose teams went 22-3 in those very same games.

While Rodgers hit the 90.0 passer rating mark in 17 of his 22 playoff games (77%), Brady did it in just 25 of his 48 playoff games (52%). Rodgers provided a quality start for his team much more consistently than Brady did. It just so happens that Brady’s teams did a better job of capitalizing on them.

Across Rodgers’ playoff games with a 90+ passer rating, his teams yielded 25.9 points per game. In the seven losses, they coughed up an astronomical 34.9 points per game.

Let’s compare that to Brady. When he posted a 90+ passer rating in the playoffs, his teams gave up just 20.0 points per game.

No single game encapsulates this phenomenon more than the 2020 NFC championship, when Brady “bested” Rodgers in their first and only playoff meeting. Brady’s Buccaneers pulled off the 31-26 road win at Lambeau Field, but Rodgers was the better quarterback by a wide margin:

- Tom Brady: 20/36, 280 yards, 3 TD, 3 INT, 73.8 rating, 5.41 ANY/A

- Aaron Rodgers: 33/48, 346 yards, 3 TD, 1 INT, 101.6 rating, 7.27 ANY/A

When will people realize that Brady’s impeccable supporting casts carried him to substantially more victories than he earned with his individual performance?

Impeccable team support

Brady does not have an argument as the most efficient regular season passer relative to his era.

Brady does not have an argument as the most efficient playoff passer relative to his era.

But he sits atop any list that has to do with winning.

He must have something to do with that, right? Maybe he was the all-time best clutch performer, and that is what allowed him out-win his peers even if his overall efficiency was similar or worse. The man was the greatest when it mattered most.

Nope, you can’t give him that distinction, either.

In his career (regular season), Brady had an 89.5 passer rating in the fourth quarter and overtime when tied or trailing by one score. Among the 61 quarterbacks with at least 300 pass attempts in this situation since 1994 (as far back as this data is available), Brady’s 89.5 passer rating placed eighth-best.

- Dak Prescott (99.7)

- Andrew Luck (96.3)

- Josh Allen (95.1)

- Patrick Mahomes (93.3)

- Tony Romo (93.1)

- Ben Roethlisberger (92.3)

- Drew Brees (91.3)

- Tom Brady (89.5)

- Derek Carr (89.3)

- Justin Herbert (89.1)

Once again, I am not saying this is bad. Placing eighth out of 61 is outstanding! The league average in this scenario was 74.7; Brady beat it by 14.8 points. Rodgers (86.1, 15th) and Manning (81.1, 27th) trailed him in this category.

Was he the most clutch, though? At least, to a degree that warrants him winning as much as he did? When players who were better won significantly less?

No.

Brady’s passer rating in this specific clutch scenario was closer to that of Derek Carr than it was to Brees, Romo, Mahomes, and Josh Allen.

Remember the topic at hand: Is Brady the greatest of all time? It sure feels like these are the types of lists you should be No. 1 on if you are the greatest, not merely great.

Well, maybe he was the King of Clutch in the playoffs, then.

Boy, do I have news for you.

In his playoff career, when tied or trailing by one score in the fourth quarter and overtime, Brady had an 84.8 passer rating. This ranks 14th among the 34 quarterbacks with at least 20 pass attempts in this situation since 1994.

- Kurt Warner (143.4)

- Patrick Mahomes (114.6)

- Brock Purdy (104.9)

- Eli Manning (104.2)

- Tommy Maddox (97.7)

- Drew Brees (95.3)

- Aaron Rodgers (94.4)

- Matthew Stafford (91.6)

- Jeff Garcia (89.8)

- Matt Ryan (87.0)

- Russell Wilson (86.5)

- Dak Prescott (85.7)

- Stan Humphries (85.4)

- Tom Brady (84.8)

- Alex Smith (84.8)

Brady did not win seven rings and 17 division titles because he is the greatest quarterback of all time, or even the greatest clutch performer. Rather, Brady is the greatest winner of all time because he had the greatest support of all time. His supporting cast is the sole reason he did so much winning despite his individual production being similar to or worse than fellow superstars who had less team success.

In just about every area that was outside of his control, Brady received elite support. His job was flat-out easier than most (if not all) quarterbacks.

Defense

Brady benefited from consistently elite defenses throughout his career. Most of his peers had to score more points to win games than he did.

To evaluate each quarterback’s defenses, we are going to use the DVOA metric, courtesy of FTN Fantasy (formerly via Football Outsiders). This metric evaluates how efficiently a defense performs on each play relative to league-average expectations in that situation. It accounts for variables such as field position, down-and-distance, score, and time, among others, which means it rates the defense’s production independent of the offense’s impact.

In other words, it is a much more accurate metric than points per game. Having a great offense can help limit opponent points by setting up the defense with great field position (and vice versa if the offense is poor). DVOA accounts for these effects. Thus, it is a good tool for understanding how a quarterback was helped or hurt by his defense.

Let’s refer back to the same group of 12 quarterbacks from earlier. Here are their teams’ average rankings in defensive DVOA (in seasons where the QB started at least 8 games). For Anderson and Fouts’ pre-1978 seasons, PPG was used, as DVOA is only available from 1978-present.

Joe Montana and Steve Young benefited immensely from the dominant 49ers defenses of the ’80s and ’90s. After that, though, it’s Brady who sits apart from the pack as the best-supported quarterback in terms of defense. His teams had an average defensive DVOA ranking of 12.6 (third of 12), finishing with a top-15 ranking 77.3% of the time (second of 12).

Compare this to Fouts and Marino. They had to overcome subpar defenses for the majority of their careers. With Fouts’ teams allowing 28 points per game in his playoff losses and Marino’s allowing 34.5, it is unsurprising that neither player won a ring.

The bottom two players on this list retired without rings. The top three players combined for 12 of them. News flash, Brady fans: Football is a team sport!

Brady’s support does not stop at defense.

Special teams

Brady constantly enjoyed elite special teams play, too.

With special teams guru Bill Belichick at head coach for most of his career, Brady’s teams produced plenty of return yardage and did not allow much of it to the opponent, frequently putting him in better positions to succeed than the quarterback on the other sideline. Brady also enjoyed clutch kicking from multiple historically great kickers, helping him seal more wins than he deserved based on his play.

Here is each quarterback’s average ranking in special teams DVOA.

Interestingly, many of the all-time great quarterbacks received poor special teams support in their careers. Brady, though, was consistently buoyed by his special teams. The same goes for Mahomes.

During his Patriots career, Brady’s teams had an average special teams DVOA ranking of 8.3. This number was dragged down by his three-year run in Tampa Bay, where each team finished 26th or worse. Overall, though, Brady’s life was made easier for the better part of two decades in Foxborough.

Special teams impact can be difficult to notice on the surface, but it has a sneaky effect between the lines. With Brady benefiting from consistently stellar special teams for 18 seasons with the Patriots, it is likely a major reason why he constantly won more games than quarterbacks who performed similarly or better.

This is especially true in comparison to his two greatest rivals, Rodgers and Manning. Rodgers had one team finish top-15 in special teams DVOA in his career. Manning had two. Over the course of their long careers, special teams was the difference in plenty of losses that would have been wins with a special teams unit of Brady’s caliber.

Here is a side-by-side look of each team’s defensive and special teams support.

Brady is the only member of the group whose teams had an average ranking better than 13.0 in both phases.

This is further evidence as to the real reason Brady was such a great “winner.” He played on the best teams. Period.

Field position

As a product of the elite defenses and special teams units that he played with, Brady had to drive shorter fields than his rivals.

Brady’s teams had an average ranking of 8.2 in average starting field position on offense. They ranked top-10 in 15 of his 21 seasons as a starter, including top-five finishes in 11 of 21 seasons. Yes, you read that correctly: more than half of his time in the NFL, Brady received top-five field position.

From 2001-19, the Patriots started their average offensive drive at their own 32-yard line, best in the NFL.

It’s a lot easier to score when the field is only 68 yards long.

Field goal luck

A natural-born competitor with the heart of an untamed lion and the hunger of a thousand polar bears, one of Brady’s best skills was his ability to motivate his kickers into making field goals. He also excelled at using his intimidating glare to force opposing kickers into missing.

Here is a look at each NFL team’s field goal percentage and opponent field goal percentage across Brady’s tenure as New England’s starting quarterback (2001-19).

This is unfathomable.

New England’s second-ranked field goal percentage of 86.2% is unsurprising. With Adam Vinatieri and Stephen Gostkowski, Brady always had a clutch leg ready to seal a victory for him.

But the 76.8% opponent field goal percentage? Some sort of dark magic is at play here.

No other team in the NFL saw its opponents make less than 80% of their kicks. Somehow, the Patriots’ opponents were more than three points below that mark.

Combine it with their own elite kicking, and the Patriots had a field goal percentage margin of 9.4%. This was 5.6 points ahead of the second-ranked Colts, the same distance between the Colts and the 24th-ranked Rams.

Once again, we have clear evidence that Brady’s pedigree as a seven-time Super Bowl champion is a stroke of luck due to the immaculate support he received, not a direct result of his actual performance at the quarterback position.

How often was he the league’s best QB?

Part of being the “GOAT” should entail a long stretch as the league’s best player.

How often was Brady actually the best player in football?

Brady would sporadically have an outstanding year, namely his MVP campaigns in 2007, 2010, and 2017. In between, though, he would have long stretches where he was just “great” from a production and accolades standpoint, rarely “the best.” Other quarterbacks in Brady’s era spent more time being viewed as the league’s QB1.

Across 22 seasons after becoming a starting quarterback, Brady was named MVP only three times. Aaron Rodgers and Peyton Manning each won more MVPs in fewer seasons. Rodgers has four MVPs in 17 seasons, while Manning had five MVPs in 18 seasons.

Another measure of the league’s best quarterback is a first-team All-Pro appearance. Brady had three of these, each coming alongside his MVP awards. The same goes for Rodgers, who had four, each coming with an MVP. Manning, though, had seven first-team All-Pro appearances, adding two more in seasons where he did not win MVP.

That gives us the following tally:

- Brady: 3 first-team All-Pro in 22 seasons: 14%

- Rodgers: 4 first-team All-Pro in 17 seasons: 24%

- Manning: 7 first-team All-Pro in 18 seasons: 39%

Lamar Jackson already has the same number of first-team All-Pro nods as Brady. Brett Favre, Steve Young, Joe Montana, and Dan Marino also had three first-team All-Pro appearances.

From a statistical standpoint, Brady did not spend much time atop the league leaderboards in efficiency-based categories. He’s got four passing yardage titles and five passing touchdown titles, but he only led the league in passer rating twice. He has just one completion percentage title and one yards per attempt title – both coming in 2007.

Outside of Brady’s historic 2007 season (maybe the greatest QB season of all time, to his credit), he never led the NFL in completion percentage or yards per attempt. The only other time he led the league in passer rating was in 2010. That makes it just two seasons (2007 and 2010) where he was No. 1 in at least one of completion percentage, yards per attempt, or passer rating. Compare that to Warner (3), Fouts (4), Rodgers (4), Manning (5), Montana (5), Anderson (5), Young (6), and Brees (6).

Who is the GOAT?

Tom Brady is one of the best quarterbacks in NFL history.

It is ignorant to pretend he is the shoo-in No. 1 and that counterarguments are invalid.

There is no definitive way to rank athletes on these all-time lists, especially in team sports. Brady’s placement comes down to a matter of personal preference. What matters to you as a sports fan?

If you are all about winning, he’s No. 1. If you value longevity and cumulative totals, he’s No. 1.

But if we’re ranking them based on how good they were at playing quarterback, you’ve got the wrong guy.

When evaluating quarterbacks solely on their individual era-adjusted performance, adjusting for team support and paying no regard to team success… Tom Brady is not the GOAT by any measure.

Brady’s era-adjusted regular season efficiency is around the 10th-best of all time, and is not close to No. 1. Some will try to argue that he is better than some of the quarterbacks ranked above him, regardless of what the stats say. However, considering how well he was supported throughout his career, it is hard to argue he was somehow better than his stats suggest. If anything, his stats were propped up by the utopian New England environment.

Adding the playoffs into the conversation only makes Brady look worse. His production took a steeper nosedive in the playoffs than most of the other similarly talented quarterbacks in league history. He was lucky to win as many playoff games as he did, as evidenced by his shockingly good records in games where he performed poorly.

Brady’s numbers are already quite far from the No. 1 spot in just about every category that is not a counting stat. Further hurting his GOAT case, Brady’s individual impact is bogged down by his consistently elite support regarding defense, special teams, field position, and kicking – not to mention the Hall-of-Fame weapons and beastly offensive lines he played with, which we did not discuss today due to the difficulty of quantifying them, but were undoubtedly present.

Brady had substantially better win percentages than other elite quarterbacks in situations where they performed at the same level. This makes it pretty clear that his team-based accolades should not be included in his GOAT case. If anything, it hurts his case, because it shows how easy he had it – especially in comparison to rivals like Rodgers, Manning, Brees, Fouts, and Marino, who were often dealt brutal hands in terms of defense, special teams, or both.

Who is my GOAT, you ask?

I have a hard time choosing one, but I think there are only two candidates: Aaron Rodgers and Peyton Manning.

- I believe they have the two best era-adjusted statistical resumes outside of Young and Montana, who (while undoubtedly great) benefited from an all-time-great system, consistently dominant defenses, and the GOAT wide receiver

- Each had many seasons as the NFL’s QB1; they are the only two post-merger QBs with 4+ first-team All-Pro appearances or 4+ MVPs

- Neither was propped up by constantly elite defenses and/or special teams

- They stood out from the pack in perhaps the most crowded era of elite QBs in league history

- Both pass the eye test as legitimately mesmerizing and gifted QBs who carried their teams rather than vice versa

Manning’s advantage over Rodgers is that he has more MVPs and first-team All-Pro seasons. Rodgers’ advantage is that he performed much better in the playoffs and in the clutch.

I’m not enough of a hot-take artist to pick a name and stand on it. To me, Rodgers and Manning are interchangeable as the GOAT quarterback. Take your pick between those two, and you cannot go wrong. I would put it this way: If you like pure arm talent, Rodgers is your guy, and if you like cerebral mastery, Manning is your guy.

(See? If I were a biased Jets fan, I would not laud the guy who spurned the Jets in 1997 – then gave them Adam Gase in 2019 – and the guy who just tanked the franchise over the last two years.)

Patrick Mahomes is on pace to join the conversation someday. His career to date already has him in the mix, although it would be unfair to include him this early on. The key for Mahomes is to sustain what he’s been doing for another decade, especially in the playoffs.

Tom Brady?

Show me one list with Brady on top – that is not a counting stat or a team accomplishment – and perhaps I will reconsider.