Ed Reed. Kyle Hamilton.

These are just a couple of the renowned names that Ohio State safety Caleb Downs is often compared to.

Downs, the top safety prospect in the 2026 NFL draft, and perhaps the best overall player, has ignited philosophical debates about the value of the safety position.

The New York Jets own the second overall pick and are likely to use it on the first non-quarterback of the draft. Downs seems like a realistic target, given he may be the strongest prospect in the class relative to his position.

The question is, could said position justify the second overall pick?

Here are two reasons the Jets should answer with a resounding “no”.

1. Salary cap value

The first, and arguably least subjective, reason it is unwise to take a safety with the second choice is the salary cap ramifications.

The No. 2 overall draft choice is not a small financial commitment. That player will immediately be making an eight-figure salary.

So, from an overarching team-building lens, it is important for teams to consider which position they are allocating that type of investment to. The more premium the position, the more value-per-dollar that the player can provide. This is a big reason why teams often reach for quarterbacks early.

The rookie wage scale is determined by draft slot. The player’s position has no bearing on the contract he receives.

A safety chosen second overall would get the same contract as an edge rusher. Yet, relative to their position, a safety chosen second overall would be a far worse value for his team than an edge rusher.

According to Spotrac, the second overall pick in the 2026 draft is projected to earn a four-year, $52.5 million deal. The average annual salary is $13.1 million, and the first-year cap hit is $9.3 million.

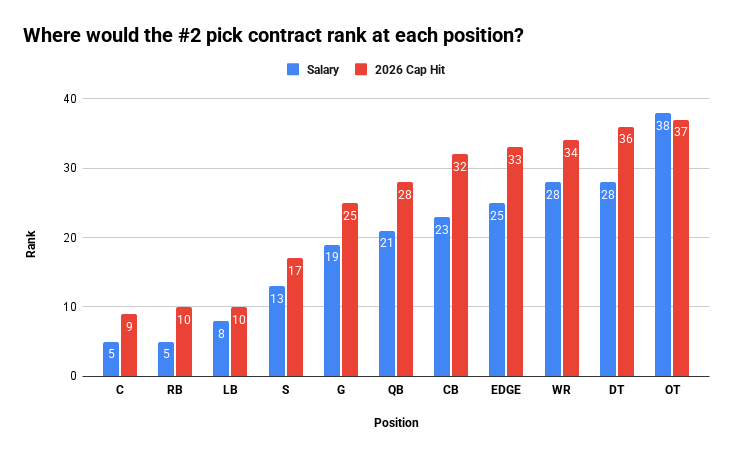

Here is where those numbers would rank at each position (based on current contracts as of Feb. 17, 2026):

- C: 5th in salary, 9th in 2026 cap hit

- RB: 5th in salary, 10th in 2026 cap hit

- LB: 8th in salary, 10th in 2026 cap hit

- S: 13th in salary, 17th in 2026 cap hit

- G: 19th in salary, 25th in 2026 cap hit

- QB: 21st in salary, 28th in 2026 cap hit

- CB: 23rd in salary, 32nd in 2026 cap hit

- EDGE: 25th in salary, 33rd in 2026 cap hit

- WR: 28th in salary, 34th in 2026 cap hit

- DT: 28th in salary, 36th in 2026 cap hit

- OT: 38th in salary, 37th in 2026 cap hit

Keep in mind that teams only start one quarterback (as opposed to at least two starters at most of the other positions), so the No. 2 pick contract for a quarterback would be the equivalent of ranking 42nd in salary and 56th in cap hit at a position with two starters, which makes it by far the most valuable position to select second overall.

The same goes for centers and running backs (one primary starter), so the No. 2 pick contract for a center or running back would be the equivalent of having the 18th and 20th-highest cap hits, respectively, at two-starter positions.

After making those adjustments, the 17th-place ranking in immediate cap hit for a safety chosen No. 2 overall would be the second-highest among the 11 offensive and defensive positions, behind only off-ball linebackers (10th).

The Jets’ decision at No. 2 is primarily between Downs, three edge rushers, and a wide receiver (Carnell Tate). Clearly, taking an edge rusher or a wide receiver would be much more financially responsible.

Think about it like this: If the Jets take Downs second overall instead of, say, Arvell Reese, then they have to fill Reese’s spot in the edge rotation. That player will cost significantly more than the safety the Jets would have to replace Downs with if they took Reese instead.

Here is a rudimentary breakdown of the impact this can have on a team’s cap picture. The placeholder salaries for free agents were chosen using the current 32nd-ranked cap hits at each position.

- Jets take Downs: S-Downs ($9.3M) + EDGE-Average vet FA starter ($10.1M) = $19.4M total

- Jets take Reese: S-Average vet FA starter ($3.9M) + EDGE-Reese ($9.3M) = $13.1M total

That’s a $6.3 million difference in cap dollars for the 2026 season. Essentially, you can add an extra solid starter (or two low-end starters/high-end backups) with the money that would otherwise be wasted by selecting a non-premium position at No. 2 over a premium position.

Defenders of selecting Downs at No. 2 may attempt to justify the concept by claiming that he transcends the non-premium status of his position, providing enough impact to eclipse the cap ramifications.

But that ignores the harsh reality that hamstrings any safety in today’s NFL.

2. Safeties cannot dominate games like they used to

Who is the best safety in today’s NFL?

Most would probably answer Kyle Hamilton. Most would be right.

Hamilton is an incredible player. Since being drafted in the first round by the Ravens in 2022, Hamilton has earned three All-Pro nods in four seasons, including first-team appearances in 2023 and 2025.

He is clearly the cream of the crop at his position.

But may I read off some of his numbers from the first-team All-Pro campaign he just put together in 2025?

- 0 interceptions (3 TD allowed in coverage, per PFF)

- 0 fumble recoveries

- 1 sack

- 2 forced fumbles

- 7 tackles for loss

- 9 passes defended

- 105 total tackles

If this is the best a safety can do in today’s league… would you really want this player with the second overall pick? Rather than someone who could be a double-digit sack machine or a perennial 1,200-yard receiver?

This is not to say that Hamilton is not a great player, or that he is not the best safety in football. Hamilton fares much more admirably in advanced metrics, such as coverage stats and Pro Football Focus’ grading system.

However, those metrics merely indicate that Hamilton is elite at executing his role on a play-to-play basis. While it is valuable to have safeties who can do that (especially at his level), Hamilton’s uninspiring numbers in traditional categories underscore the reality that safeties, no matter how good, cannot maintain an omnipresent impact on games the way that edge rushers and wide receivers do.

They just don’t make many game-altering plays.

It didn’t used to be this way. But the game has changed.

Back when Ed Reed was snagging eight-plus interceptions in his sleep, and Troy Polamalu was running around taking heads off while tossing in seven picks to boot, the NFL was a much different game. Vertical passing was all the rage, more leeway was allowed on hits over the middle, and Cover 1 defenses were more popular. Safeties had many opportunities to make game-changing plays each week, whether it was via an interception or a big hit.

In today’s game, teams are getting the ball out quicker and shorter than ever before. Cover 2 has become the predominant coverage look, eliminating deep shots and encouraging short passes. It also forces safeties to sit back and play half the field, focusing on keeping things in front of them instead of being rangy and pursuing plays. Above all, offense-friendly rule changes have discouraged safeties from flying in and making big hits.

It all equates to a drastic decrease in the amount of playmaking opportunities available to safeties.

In 2003, Reed’s second NFL season (when he snagged seven picks to make his first All-Pro appearance), the league-average interception rate was 3.3%. By 2025, it had dropped to a record-low 2.2%, two-thirds of where it was in Reed’s second year.

Put another way, a pick was thrown once every 30.7 passes in 2003, compared to once every 45.9 passes in 2025. That’s an enormous difference, and it directly impacts safeties more than any other position.

The rise of Cover 2 (and zone coverage in general), the emphasis on quick passing, and the rampant introduction of offense-friendly rules have made interceptions rarer than ever, especially on deep passes, preventing talented safeties like Hamilton from making highlight-reel plays at the same rate as the legends who came before them. It’s not a slight on the talent of Hamilton, his peers, or a prospect like Downs—it’s just a consequence of the game’s evolution.

Meanwhile, nothing has stopped edge rushers and wide receivers from dominating just as much, if not more, than ever.

Interceptions have gone to the wayside, but sacks haven’t. NFL teams took 2.4 sacks per game in 2025, even higher than 30 years prior (2.2 in 1995) or 20 years prior (2.3 in 2005). Whereas today’s safeties do not have the chance to replicate the likes of Reed, modern pass rushers like Myles Garrett and T.J. Watt have just as much of an opportunity to wreck games as Reggie White or Michael Strahan did in their day.

There have been many world-class wide receivers in NFL history, and they are only becoming more dominant in the modern game. Seven of the 27 all-time best single-season performances in receiving yards per game by wide receivers (min. 10 games, 1966-present) have occurred in the 2020s, coming from six different players.

Superstar edge rushers and wide receivers are omnipresent in a football game. The opponent has to account for them on every play. If you don’t double-team them or adjust your game plan in some other way to reduce their impact, they will keep coming at you. That makes their teammates better, as everyone around them can enjoy more favorable opportunities due to the attention allocated to the star. This is factored into their overall impact and, thus, their financial valuation.

The same doesn’t go for safeties. They can be avoided without allocating extra resources to them. Oftentimes, they are uninvolved in the play, just sitting back in zone coverage somewhere. They are more of a cog in the machine than an engine. Thus, there isn’t much that they can do to make their teammates better, which further decreases their value to a team, even beyond their lack of individual impact.

All of this is reflected in positional spending across the league. Edge rushers and wide receivers make the big bucks, while safeties are an afterthought, because that’s just how today’s game works. It’s not that safeties don’t matter; it’s just that the way the game is played prohibits them from impacting the game to nearly the same degree as many other positions.

Even if Downs were a perfect safety prospect who was guaranteed to be the league’s top safety immediately, his impact would arguably still be less than that of the 10th-to-15th-best edge rusher or wide receiver. No matter how much you like Downs, he is not going to come into the NFL and light up the highlight reel. If guys like Hamilton and Derwin James often fail to get more than a single interception over a full season in today’s league, so will Downs.

After all, even Hamilton (14th) and James (17th), who were highly touted safety prospects in their own right, were selected nowhere near the second overall pick.

The best a safety can do in today’s league is to avoid busting coverages and consistently wrap up their tackles. There is plenty of value to those skills if they can be executed at a high degree of consistency, but big plays are a rarity from them. They cannot take over games. And with the second overall pick, you should want a player with the ability to take over games and win them single-handedly.

Safeties can’t do that in 2026, no matter how great.

Selecting Downs second overall would be an unwise move by the Jets, both from a financial and football perspective.