The true run-stopping consistency of every New York Jets defender in 2022

A few weeks back, I unveiled my run-blocking statistics for the 2022 New York Jets offense after rewatching and charting every run play from the Jets’ 2022 season. The goal was to quantify the run-blocking production of every player by assigning positive credit for good blocks that spurred successful runs and assigning negative credit for poor blocks that caused unsuccessful runs.

Now it’s time to shift our focus to the opposite side of the ball.

I rewatched the film of every run-defense snap from the Jets defense in the 2022 season. The goal was the same as it was for the run-blocking exercise: to quantify every player’s run-defense impact by tallying up their totals of positive and negative plays.

Run defense is a facet of football that does not get analyzed correctly by the masses. Yes, we do have some easily accessible stats that can be used to analyze run defense, such as total tackles and contextualized tackle stats like tackles for loss and run stops. These stats can tell us a little bit about a player’s impact against the run.

But the problem is not a lack of available stats (as is the issue with run-blocking). The problem is that the stats we are using do not even come remotely close to painting an accurate picture.

There are two major issues with using tackle totals (even if they are contextualized) as a tool for evaluating a player’s run defense:

1. You do not have to make the tackle to help stop a run.

Whether it’s creating penetration, eating a double team, preventing a blocker from getting to the second level, holding the point of attack, setting the edge, or stringing a run out to the sideline, there are so many ways to help stop a run without being the player who actually gets credit for making the tackle. In fact, very commonly, the player primarily responsible for causing a run’s failure is not the player who made the tackle. Players deserve just as much credit for these off-the-stat-sheet plays as they do for making tackles.

2. We have to account for negative plays to understand a player’s cumulative impact.

What if we only looked at a quarterback’s touchdown total while ignoring his interception total? What if we only looked at a cornerback’s interception total while ignoring how many yards and touchdowns he allowed? This is essentially what we are doing when we look solely at a player’s total number of TFLs or run stops. To truly gauge a player’s impact against the run, you have to know the ratio between how many plays he makes and how many plays he gives up. It’s just like anything else in sports.

Without further ado, let’s dive into my charting for the Jets’ 2022 run defense.

Explaining the run-defense stats

My main goal was to find each defender’s ratio between good plays and bad plays. This would give us a solid gauge of each player’s run-defense consistency.

I rewatched every run the Jets faced this season that was not a QB sneak, a QB scramble, or a run on third-and-very-long that was not intended to gain a first down. If a run was unsuccessful, I gave credit to the defenders who contributed to making the run unsuccessful. On successful runs, I attributed blame to the defenders who contributed to allowing the run’s success.

This is my criteria for a successful run: Gains at least 40% of the required yardage on first down, gains at least 60% of the required yardage on second down, or picks up the conversion on third/fourth down.

If a run meets one of those criteria, it is a success, and I dole out negative credit to the defenders responsible. If a run does not meet one of those criteria, it is a failure, and I dole out positive credit to the defenders responsible.

How did I decide what constitutes a rep that deserves positive credit for creating an unsuccessful run? To me, a defender deserved credit if they directly contributed to denying the runner an opportunity to create a successful run. This could be a strong edge-set, impactful penetration that forces the runner to re-direct, eating a double-team, or any of those subtle things. And, yes, I still credited players for making the tackle – I did not do this exercise to solely focus on off-the-stat-sheet stuff. I just wanted to include both the tackles and the off-the-stat-sheet stuff.

How did I decide what constitutes a rep that deserves blame for allowing a successful run? Gap control is the most common thing I looked for. For a run to be successful, someone had to lose their gap responsibility. Did you cheat too far inside/outside? Did you misread the play? Did you allow the blocker to move you out of your gap?

I also commonly blamed defenders if they missed a tackle or if they failed to hold their ground and were moved too far off their spot (think of what a great block would look like from the offense’s perspective).

Multiple players could be charted on any positive or negative play. In fact, on the majority of runs, I charted more than one player. Run-defense is a team effort.

I want to be clear that this exercise is subjective. I am not in the huddle, so it is sometimes difficult to know with 100% certainty what the players’ gap responsibilities are.

Additionally, subjectivity often comes into play in 50-50 type situations where it’s not obvious how a play should be judged. There are often times when I might think a player deserves credit while someone else may not be impressed, or times when I think a player should be blamed and someone else would cut him slack.

These results are simply my perception of what happened after analyzing each play on film. If every football analyst in the world did this same exercise, they would each come out with slightly different results.

With that being said, it’s fairly straightforward on most plays to identify who deserves credit/blame, so I still feel extremely confident in the validity of the results I came out with.

Examples

Before we get to the numbers, let’s take a look at two plays to exemplify how everything works.

This run by Najee Harris on first-and-10 goes for a loss of 3 yards. Obviously, this is an unsuccessful run. I credited Quinnen Williams (#95), Sheldon Rankins (#98), and C.J. Mosley (#57) for making it happen.

First, watch how Williams drives the center (#61) into Harris’ lap and immediately blows up the play. Everything starts there. Then, Mosley and Rankins beat their blockers to rally and make the tackle. All three players had a part in making this happen, but in the box score, only Mosley and Rankins got credit. Williams got no statistical credit despite being the primary driving force. This exact play is what inspired me to do the entire exercise.

Next, we have a 7-yard run by Samaje Perine on first-and-10. This is a successful run. I blamed Solomon Thomas (#94), Marcell Harris (#36), and Jordan Whitehead (#3) for allowing it to happen.

This hole opens up because Thomas allows the right guard to get across his face and pin him to the back side. Then, Harris gets blocked to the back side. He still has a chance to make the tackle but misses. Whitehead comes in unblocked but also misses a chance to stop Perine for a short gain.

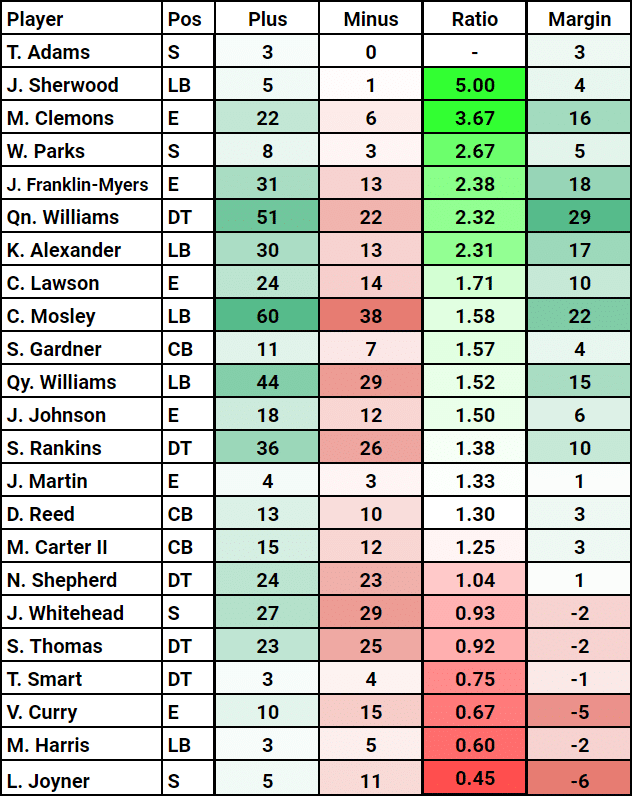

Complete run-defense numbers for the 2022 New York Jets

Here it is: The number of plus plays and minus plays for each Jets defender against the run in 2022.

For reference, my educated guess is that the league average plus-to-minus ratio would be somewhere around 1.3-to-1 if I did this study for the whole league. It is impossible to know for sure, but that seems to be a reasonable benchmark.

I based this on two things:

- The league average rushing success rate, using the criteria I laid out above, is approximately 50%. This means the average team is expected to have approximately the same number of successful runs and unsuccessful runs.

- On average, I tend to positively credit about 2.2 defenders per good play and negatively credit about 1.7 defenders per bad play. These numbers likely wouldn’t change much if I did the study for the whole league.

So, if the average team has the same number of successful and unsuccessful runs, and each successful run yields 2.2 positive credits while each unsuccessful run yields 1.7 negative credits, that translates to a ratio of 1.3-to-1.

Let’s look at these numbers in a different way. Here, we will see the cumulative value that each player provided.

In this list, players are ranked based on the difference between their actual plus-to-minus margin and the margin they would be expected to have with a league-average ratio (1.3-to-1) over the same sample of plays. In other words, this is an estimation of their total run-defense value over the estimated league average, quantified by the number of run plays they saved over average (seen in the “Value” column).

Takeaways

Statistically, the Jets were solid at stopping the run in 2022. They ranked 10th-best in fewest yards allowed per rush attempt (4.2) and 10th-best in rush defense DVOA (-12.5%). It seems clear New York’s run defense was good, but not great.

My charting seemed to back that up. Among the plays I charted, I had the Jets giving up a successful run 47.2% of the time, which is slightly better than the typical league average of 50% (the top teams are in the low-40s). Cumulatively, the Jets’ defenders combined for 470 positive reps and 321 negative reps, a ratio of 1.46-to-1 that slightly beats my estimated league average of 1.3-to-1. They also combined for 43.1 total plays saved over average, which amounts to saving about 2.5 successful runs per game.

All of that seems to line up perfectly with the Jets’ No. 10 rankings in yards-per-attempt and DVOA. They were a good run defense. Not elite, but good.

The chart above does a good job of illustrating where the impact was coming from. It shows us which players led the Jets’ run defense to success and which players held them back from being elite. Most of the positive impact came from Quinnen Williams, the edge defenders, and the linebackers. Meanwhile, the Jets were hamstrung by the woes of their starting safety duo and their second-string defensive line.

I’ll go player-by-player and give a brief overview of what I saw. We will start with their most valuable run defender (Quinnen Williams) and work our way down.

1. DT Quinnen Williams (2.32 ratio / +19.2 total plays saved)

As expected, Williams’ film backed up my hypothesis that he was the Jets’ most dominant run defender.

Williams did not have the most otherworldly tackle stats in the box score, but on film, you could see the subtle-yet-profound impact he was making on a down-to-down basis. Williams consistently swallowed up double teams and held strong at the point of attack, making life easier for everyone else on the Jets’ defense.

2. EDGE Micheal Clemons (3.67 ratio / +12.3 total plays saved)

Clemons was the greatest revelation of this study. I knew he was good against the run this year, but I didn’t realize he was this good. Clemons shined with his combination of length, power, motor, and technique. He consistently dominated tight ends. Fundamentally, he showed a great understanding of his gap assignments, rarely making a mistake in that area.

Clemons is already an extremely good run defender.

3. EDGE John Franklin-Myers (2.38 ratio / +12.1 total plays saved)

I was a vocal advocate of moving John Franklin-Myers to defensive tackle both prior to the 2022 season and throughout the first few weeks of the year. However, after re-watching the film of the Jets’ 2022 run defense, I now understand their vision with Franklin-Myers on the edge.

JFM is a fantastic run defender on the outside. His size and strength make him extremely difficult to move relative to most other edge defenders. I saw so many plays in which Franklin-Myers set a firm edge on the front side and redirected the runner back inside toward the traffic, where he was stuffed by someone else.

This skill made Franklin-Myers a weapon against outside-zone plays, where he was stupendous at stopping the lateral momentum of the play to ruin the entire blocking scheme. It was a domino effect – in a very literal sense. Picture No. 91 on the right side edge stopping the tight end in his tracks. Then, the right tackle bumps into the tight end. After that, the right guard bumps into the right tackle. And so on.

After this film review, I’m no longer critical of how the Jets use Franklin-Myers. I see exactly what they saw in Franklin-Myers when they decided he could be a full-time edge defender (with occasional pass-rush snaps on the interior).

4. LB Kwon Alexander (2.31 ratio / +11.2 total plays saved)

Alexander’s run defense took me by surprise. When the Jets signed him, I thought they were getting a strong coverage player who would struggle against the run, but Alexander’s run defense was very good this year.

Something Alexander constantly excelled at was lowering his shoulder and taking on blockers in space. Alexander often found himself matched up on the edge or at the second level with a tight end, fullback, or climbing offensive lineman, and he was superb at taking them on with aggression and stopping them in their tracks. Runners would often count on their blockers to clear Alexander out, but Alexander would drop his shoulder and stonewall the blocker where he stood, creating congestion that caused the runner to be stuffed.

5. LB C.J. Mosley (1.58 ratio / +8.9 total plays saved)

Mosley had a solid year. I wouldn’t say his run defense was great (his All-Pro nod was probably a bit generous), but on the whole, he was pretty good.

There were times I felt like Mosley should have been a bit more aggressive at shooting his gap and trying to stop a run near the line of scrimmage. He tends to be conservative in pursuit. This has its benefits, as it helps Mosley avoid overshooting plays and minimize the number of explosive runs he allows, but there’s a time and place where aggressiveness is smart and I feel like Mosley did not do it often enough.

On the positive side, I loved Mosley’s evasiveness and block-shedding in space. Mosley was difficult to block at the second level, showing an arsenal of moves to dodge blockers and keep himself clean to make tackles. This is easily his best trait as a run defender. I would say he is elite in this specific area.

6. LB Quincy Williams (1.52 ratio / +5.2 total plays saved)

Williams really impressed me in this film review. He demonstrated remarkable improvement over the previous season.

I was not a fan of Quincy’s game in 2021. Fans fell in love with his propensity for highlight-reel hits, but many of them did not realize those hits came at the cost of far too many mistakes. Williams was a reckless player who sacrificed consistency for the occasional splashy play.

But in 2022, Williams was significantly more sound and reliable. His discipline, gap control, and play recognition were all so much better.

7. EDGE Carl Lawson (1.71 ratio / +4.9 total plays saved)

Lawson was easily the most surprising player of this study. My hypothesis was that he played poorly against the run this year, but the film proved otherwise. He was pretty solid overall.

Lawson got off to an ice-cold start against the run but finished red-hot. Through Week 7, I had him with 5 positive plays and 10 negative plays (0.50 ratio). Over his final 10 games, I had him with 19 positive plays and 4 negative plays (4.75 ratio).

Early in the year, Lawson often gave up the edge as he got caught playing too aggressively to the inside. He fixed this around mid-season and started playing with much better discipline in the run game.

I still believe the Jets would be best served cutting Lawson (it just makes too much sense financially), but after watching the film of his run defense, I am now slightly more open to the idea of keeping him. It seems Lawson is not a liability against the run as I previously thought he was.

8. S Will Parks (2.67 ratio / +3.5 total plays saved)

Parks impressed in his limited appearances. He played with an extremely aggressive downhill mentality from the safety spot, blowing up a handful of runs to the outside.

9. LB Jamien Sherwood (5.00 ratio / +3.2 total plays saved)

Sherwood only played 25 defensive snaps all season and managed to earn 5 positive credits. He reminded me of Mosley in his limited action. Sherwood is not the greatest athlete and plays with a more patient mentality, so he will not make many splashy plays charging into the backfield, but he showed some good play recognition and evasiveness at the second level.

Putting too much stock into 25 snaps would be silly. Regardless, Sherwood looked good in his limited action. Let’s see if he can keep that going throughout training camp and the preseason this year.

10. S Tony Adams (3-0 ratio / +2.6 total plays saved)

Adams is another small sample stud, recording 3 positive credits and 0 negative credits over 118 defensive snaps. Most of those snaps (104) came in Weeks 17 and 18.

Again, we should never overreact to small samples, but I was very impressed with Adams in his short time on the field. He took some outstanding angles to the ball out of the free safety position, and his finishing at the tackle point was tremendous. I’m looking forward to watching Adams throughout the lead-up to the 2023 opener.

11. EDGE Jermaine Johnson (1.50 ratio / +2.0 total plays saved)

Johnson’s ratio was one of the biggest surprises of this study. I thought he was a stellar run defender this year and expected him to score much better.

But here’s the catch: Most of Johnson’s mistakes came in the first two games. Over his final 12 games, Johnson really was a stellar run defender.

From Weeks 1-2, I had Johnson with 3 positive credits and 6 negative credits (0.50 ratio). From Weeks 3-18 (12 games), I had Johnson with 15 positive credits and 6 negative credits (2.50 ratio).

Johnson started his career against the Ravens and Browns, two elite rushing teams who particularly love to attack the outside. Baltimore and Cleveland were able to pin him inside a few times and get to the edge on his side. After that, though, Johnson was significantly better at containing the edge. He coupled his improved discipline with his length, speed, and motor to make a plethora of key tackles in the run game.

12. DT Sheldon Rankins (1.38 ratio / +1.7 total plays saved)

Rankins had a much-improved second season with the Jets. He really struggled against the run in 2021 but looked like an above-average run-stopper in his second season, which is a great complement to the juice he provides in the passing game.

The biggest area of improvement for Rankins was his recognition against traps and whams (plays in which the offense intentionally left him unblocked). These plays are designed to entice defensive linemen to charge into the backfield and take themselves out of the play. Rankins frequently took the bait in 2021. But in 2022, he was much better at recognizing these plays, consistently finding ways to blow them up.

I still wouldn’t say Rankins is a great run defender, as he can get moved far down the field on double teams, but the good outweighed the bad in 2022.

13. CB Sauce Gardner (1.57 ratio / +1.6 total plays saved)

I think Gardner is a much better run defender than these numbers let on, as he provided a lot of value in saving already-bad plays from becoming even worse – which he does not get credit for with the way I charted things in this study (one of its flaws). His hustle and angles as a last line of defense were excellent.

There were a few plays where Gardner got plowed by an open-field block. Overall, though, he did a very nice job of supporting the run. He showed a good feel for gap control, doing a great job of containing the edge and forcing runners back inside. When forced to come downhill and make a stop, his tackling was sound.

One of the potential flaws in using the 1.3-to-1 benchmark is that there would likely be a difference in the league averages for each position. I feel as if the number would be much lower for outside cornerbacks than any other position since they don’t get the chance to stuff many runs and are usually just responsible for being the last line of defense – so they would be blamed more often than they are credited.

With that in mind, if we assume the league average for cornerbacks would be much lower than 1.3-to-1, it makes Gardner’s 1.57-to-1 ratio seem elite.

14. EDGE Jacob Martin (1.33 ratio / +0.1 total plays saved)

Martin was decent against the run in his short stint with the Jets.

15. CB D.J. Reed (1.30 ratio / -0.1 total plays saved)

I was a little underwhelmed with Reed’s run defense. He was an elite run-stopping cornerback with Seattle in 2021. This year, he made more mistakes than I expected, specifically when it came to finishing tackles in one-on-one situations on the edge. The missed tackles were up this year in comparison to his Seattle days.

Still, Reed was good overall. (Remember, we’re assuming outside corners are expected to have a much worse ratio than 1.3-to-1). Reed is an eager run defender who quickly diagnoses plays and makes his way toward the action. When he hits, he hits hard.

I would expect Reed’s missed tackles to go down in 2023. This season was out of the norm for him in that area.

16. CB Michael Carter II (1.25 ratio / -0.6 total plays saved)

Carter II is a slot corner, so his standards are different than outside corners like Reed and Gardner. He often lines up close to the box and has a key gap assignment.

I would say Carter II’s run defense was average. He is a good tackler when he gets to the ball carrier, but he allowed himself to be blocked out of the lane by wide receivers more often than would be ideal.

17. DT Tanzel Smart (0.75 ratio / -1.9 total plays saved)

I would say every player from here on out had a poor season against the run.

Smart struggled in his short time on the field. Opposing offensive linemen created plenty of vertical movement on him, creating ample room inside. Smart has intriguing explosiveness but must be better at holding the point of attack.

18. LB Marcell Harris (0.60 ratio / -3.6 total plays saved)

Harris was brutal in his 62 snaps this year, missing tackles and taking bad angles. The 49ers moved him from safety to linebacker in 2021 and the Jets kept him there, but watching his film, he might be better off going back to safety.

19. DT Nathan Shepherd (1.04 ratio / -5.3 total plays saved)

Shepherd is a great athlete with exceptional explosiveness, but he relies on those tools too much. He often tries to blow by his man and shoot through gaps to make plays. While this occasionally results in a nice-looking stop, it too often results in Shepherd taking himself out of the play and clearing a gaping hole up the middle. Shepherd is also easily moved against double teams, consistently giving up at least a yard or two of vertical displacement beyond the line of scrimmage.

Shepherd will turn 30 in October. He’s had many years to figure out how to couple his physical tools with better fundamentals and discipline, yet he remains one of the least effective run defenders you will watch at the defensive tackle position. His pass rushing is fine, but his run defense is problematic. I think the Jets would be wise to go in a different direction this offseason as Shepherd becomes a free agent.

I think Shepherd is the perfect example for exposing the flaws in ESPN’s “win rate” metrics that commonly float around the internet. ESPN had Shepherd with the second-best run-stop win rate among defensive tackles this season. That is beyond silly.

However, it makes sense when you consider how ESPN tracks the metric.

ESPN calculates win rates using player tracking data. This means they are not watching the film and are making their assessments based on the movements of dots on a screen.

That is such a simplistic way of looking at things. You have to actually watch a play to see what happened. It is not necessarily a “win” if a defensive tackle gets past his blocker on a run play, and Shepherd perfectly exemplifies this. Yes, he does get into the backfield often, but it’s often because the offense wants him to. Teams love running traps and whams on Shepherd. Even when they don’t run those, Shepherd will often just overshoot the play or shoot the wrong gap, and the offensive lineman will use it against him.

I am very suspect of ESPN’s win rates, to say the least.

20. S Lamarcus Joyner (0.45 ratio / -8.1 total plays saved)

For a free safety who usually lined up deep, Joyner was involved in run-game blunders way too often. I don’t expect him to rack up positive plays from that position, but I do expect him to keep the mistakes to a minimum. Just look at Tony Adams, who posted a 3:0 in the same role.

The main issue for Joyner was the angles he took to the football. Joyner did not put himself in the right positions to make plays.

21. EDGE Vinny Curry (0.67 ratio / -8.3 total plays saved)

The Jets enjoyed great run defense from most of their edge defenders in 2022. Curry was the exception. His discipline on the edge was poor. Curry frequently found himself getting moved inside and giving up the edge.

22. DT Solomon Thomas (0.92 ratio / -8.4 total plays saved)

Thomas has all of the same weaknesses as Shepherd with even fewer splashy plays. He easily gets moved both laterally and vertically, is easily fooled by traps and whams, and is poor at finishing tackles. Thomas had a very poor season and I would be shocked if the Jets brought him back.

The Jets’ backup defensive tackle duo of Shepherd and Thomas was flat-out brutal against the run. Whenever Quinnen Williams and/or Sheldon Rankins sat, teams eagerly ran straight up the middle at Shepherd and Thomas, leading to great results.

I would like to see the Jets focus on improving their depth at defensive tackle in 2023, specifically focusing on finding two players who thrive in the run game. Depth on the defensive line is particularly important in the Jets’ scheme, as they love to rotate their defensive linemen and thus give more snaps to their backup linemen than most teams in the league.

It cannot be understated how important it is for the Jets to have four reliable defensive tackles. They rotate their second-stringers into the game a lot, and in 2022, those second-string snaps were very problematic for the Jets because of Shepherd and Thomas’ terrible run defense. You can’t afford to have two run-stopping liabilities in the middle of your defensive line for extended portions of the game.

23. S Jordan Whitehead (0.93 ratio / -9.5 total plays saved)

Whitehead’s run defense is supposed to be the strength of his game, mitigating his issues in coverage. I expected him to fare excellently in this study. However, I was surprised to see that Whitehead was actually a major liability against the run as well. He was a primary culprit on far more run plays than I realized.

Yes, Whitehead does make the occasional flashy stop near the line of scrimmage, but those are the exception. Whitehead’s consistency against the run was woeful.

Whitehead missed a ton of tackles, both in the trenches as the first player to meet the runner and as a second-level defender in space. The tackling technique is not ideal. He often dives at the legs and whiffs or lowers his shoulder and misfires.

When taking on blocks, Whitehead frequently got steamrolled and gave up a running lane, often getting blocked by wide receivers. He’s the anti-Kwon Alexander. Kwon will challenge blockers aggressively and devour them, fulfilling his gap responsibility to ensure a run is contained. Whitehead, seeking highlights, usually tries to get around defenders and pursue the ball, which leads to him either getting plowed or just taking himself out of the play. He’ll rarely hold his ground against a block. (I know Alexander and Whitehead play different positions and are 30 pounds apart; I’m just comparing their mentalities.)

The angles Whitehead took in space were often an eyesore. Don’t count on him to save the day if a run breaks past the first two levels.

Prior to this film review, I thought it was fairly likely the Jets would release Whitehead. Now, I think it is very likely. I was extremely underwhelmed by his performance in the run game. If the Jets view his film in the same light as I do, I’m not sure how they would pass up on the $7.3 million in cap space they would open up by releasing him.

Unlisted: EDGE Bryce Huff

Huff does not appear on the list. This is because he played very few snaps against the run and I did not credit him positively or negatively on any plays over his limited sample of opportunities.

Since he exclusively played in obvious passing situations, Huff was rarely on the field for a run play. Only 16 of his 191 defensive snaps (8%) came against the run, and most of those 16 plays were give-up runs for field position on third-and-forever. The Jets made sure to never place Huff on the field in situations where the run was a legitimate threat.

Huff did play the run regularly over his first two seasons, logging 220 snaps against the run across 23 games (9.6 per game). I always thought his run defense was below-average, but I never thought it was atrocious enough to where I would want to completely eliminate his early-down pass-rush opportunities just to ensure he never touches the field in a running situation.

I want to take a second look at Huff’s run defense over his first two seasons and see if it was truly bad enough to warrant the pass-only role New York cooked up for him in 2022. Stay tuned.

That’s all, folks

There you have it: My complete thoughts on the Jets’ individual run-defense performances in 2022.

Whose numbers surprised you the most?