One week ago, we dove deep into a vast sea of numbers, embarking on a quest to determine whether there were any particular metrics that could help us predict the future success of quarterback prospects in the NFL draft.

The results were fascinating. No single metric from prospects’ final college seasons had a strong correlation with their future production in the NFL. However, there were a handful of metrics that correlated with NFL success more strongly than the rest. When we combined those metrics together, we were able to concoct a surprisingly reliable formula for predicting how first-round quarterback prospects would pan out in the pros.

Now, it’s time to set out on the same journey for perhaps the second-most valuable position on the football field: edge rusher.

If quarterback is the most sought-after position in the draft, it stands to reason that the next position in line would be the one responsible for destroying quarterbacks. The New York Jets could provide an example of this hierarchy in April.

With slim quarterback options for the No. 2 overall pick, the Jets could select the draft’s first non-quarterback, and there is a good chance it will be an edge rusher. Whether it’s Miami’s Rueben Bain, Ohio State’s Arvelle Reese, or even Texas Tech’s David Bailey, the Jets have quite a few intriguing edge rushers to choose from at No. 2.

Which metrics should the Jets be looking at to determine which of those prospects has the best chance of succeeding in the NFL?

That’s what we’re here to figure out today.

Finding the most predictive metrics for NFL draft EDGE prospects

I studied the college and NFL production of the 48 edge rushers chosen in the first round of the NFL draft from 2015 to 2024.

I compiled each prospect’s performance in their final college season* across 15 different metrics, as well as their career NFL regular-season performance in four different metrics:

- Sacks per game

- Quarterback hits per game

- Pressure rate

- Overall Pro Football Focus grade

I then calculated the correlation between each college metric and each NFL metric.

*-If a prospect played an insufficient number of defensive snaps in their final college season (less than 300), I combined their production from their final season with their second-to-last season.

So, which college metrics did the best job of predicting a prospect’s chances of succeeding in the NFL?

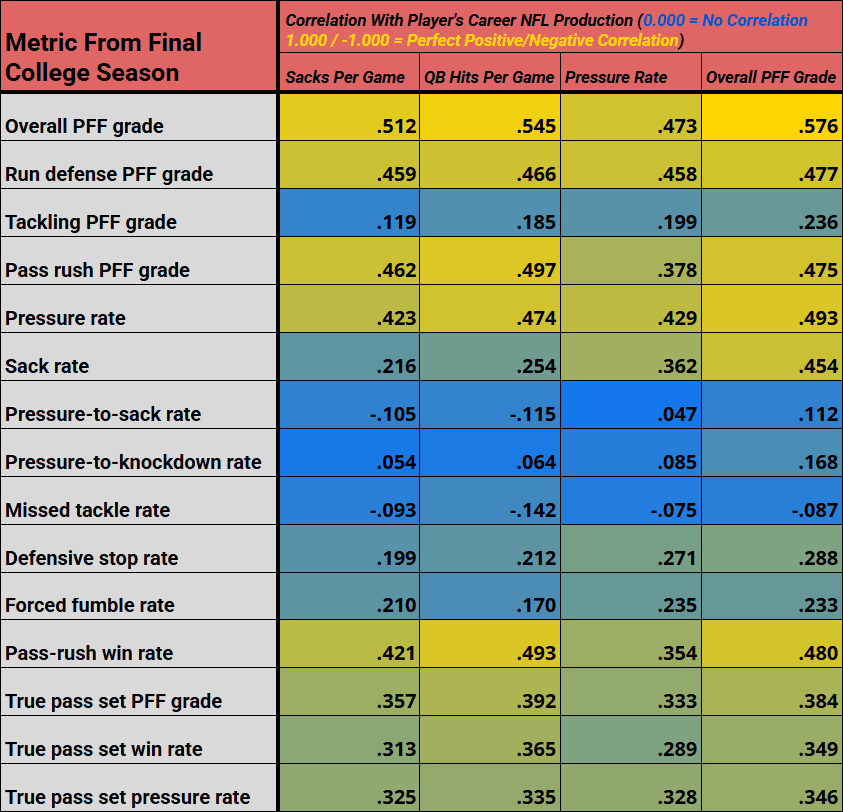

Seen below are the 15 metrics I analyzed from each player’s final college season, along with their correlation coefficient with each NFL metric. For reference, a correlation coefficient of 0.000 indicates there is no correlation; the closer it gets to 1.000 (perfect positive correlation) or -1.000 (perfect negative correlation), the stronger the correlation.

Simply put, the yellower the box, the more that college metric correlated with that NFL metric, and the bluer the box, less they correlated.

Now, these are some downright fascinating results, if I may say so myself. You’re probably rolling your eyes if you’re not a stat geek like me, but bear with me; there are some extremely interesting takeaways here.

If you read our quarterback article, you may remember that, out of the 21 metrics we analyzed, the most correlative metric (deep pass attempt rate) had a correlation coefficient of just 0.282. The majority of metrics in this table are above that mark, and significantly so in many cases.

In fact, the most correlative metric in our EDGE table—overall Pro Football Focus grade— had a correlation coefficient of over .500 for sacks per game, hits per game, and NFL PFF grade. Essentially, it is almost twice as correlative as the top metric for quarterbacks.

Simply put, there is significantly more correlation between college and NFL production for edge rushers than there is for quarterbacks. What does that mean? We’ll get into the philosophical side of this discussion later on, but first, let’s dive further into these numbers.

In general, a “strong” correlation is considered anything above 0.75. If the correlation coefficient ranges from 0.5 to 0.75, we have a “moderate” relationship. Anything from 0.25 to 0.5 is considered “weak,” and if it is below 0.25, there is essentially no meaningful relationship.

Most of the quarterback metrics had a relationship that is considered less than weak. For edge rushers, though, we have some real data to work with. Many of these metrics had a relationship that ventures close to “moderate” territory, which means there are probably some very real trends worth looking into.

Does the PFF grade tell us everything?

I included the players’ NFL outputs in sacks per game, hits per game, and pressure rate to have some more traditional metrics to refer to, if some readers would prefer to answer a question as simple as, “What metric gives me the best chance of knowing who will get a lot of sacks in the NFL?”

Ultimately, though, I think overall PFF grade is the best metric for quantifying the success of an NFL edge rusher.

Yes, it is a subjective grading system, but it does a good job of accounting for two things that go overlooked with raw box-score stats like sacks and hits: a) the context of the player’s role and situation, and b) their impact as a run defender, particularly in terms of their off-the-stat-sheet performance beyond just tackles (gap integrity and edge-setting). Other variables also get tossed in there, like coverage, pass deflections, and hustle plays.

If the question is simply, “How good is this player?”, then overall PFF grade is our best answer. We don’t truly know how “good” an edge rusher is based solely on how many sacks or hits he gets, and that is still true even if we expand all the way out to his pressure rate (per-snap efficiency at getting any type of pressure). PFF’s grading system is not gospel, but it is the best one-number quantifier for this type of analysis.

So, to simplify our examination, let’s remove sacks, hits, and pressures from the picture and focus solely on the correlation between the 15 college metrics and NFL PFF grade.

Here is how the 15 metrics stack up.

Many college metrics had a noticeable correlation, but overall PFF grade came out on top at .576. It turns out that a player’s overall PFF grade from their final college season is the strongest indicator of how they will perform in the NFL based on the same metric.

You might be thinking, “Well, that’s obvious, nerd,” but that was not anywhere close to the case with quarterbacks. In fact, in our quarterback analysis, overall PFF grade was the second-least correlative metric in the entire study, checking in with a correlation that was almost perfectly zero. Instead, niche tendency metrics, like scramble rate and deep pass attempt rate, were much better at telling us how well a quarterback would play in the NFL.

So, it is fascinating that we can find significant predictive value in edge rushers’ production, whereas for quarterbacks, raw production meant little to nothing. And that does not just apply to PFF grade. For quarterbacks, there was essentially no production metric that carried correlative weight, whether it was efficiency at various levels of the field, overall adjusted completion percentage, or avoiding sacks.

The story is much different for edge rushers. Production matters.

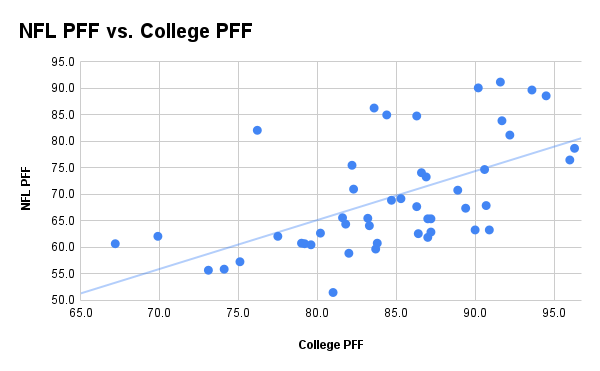

Here is a look at the 48 prospects ranked by their college PFF grades. You can see the noticeable correlation with their NFL PFF grades.

This scatter plot is a great way to visualize the relationship between the two.

It would seem shallow, though, to simply suggest, “Welp, just look at a guy’s PFF grade, and you have a good chance of predicting his college success.”

We should take this a couple of steps further. What if we combined overall PFF grade with some of the other metrics that had a noticeable correlation? After all, there were quite a few of them.

These are the metrics that had a correlation coefficient of at least .400 with NFL PFF grade:

- Overall PFF grade (.576)

- Pressure rate (.493)

- Pass-rush win rate (.480)

- Run defense PFF grade (.477)

- Pass rush PFF grade (.475)

- Sack rate (.454)

The run defense and pass rush grades factor into the overall PFF grade, so we can toss them aside. That leaves us with a clear top-four metrics that have the most value in predicting how good a first-round edge rusher will be in the NFL.

Let’s combine the top four most correlative metrics into a “Big 4”: overall PFF grade, pressure rate, pass-rush win rate, and sack rate.

The Big 4

I rated each of the 48 prospects on a 0-100 scale for their performance in each of the four metrics (the worst player in the group received a zero, the best received a 100, and the rest of the players were scored relative to the top player). I combined those four numbers into one “Big 4 Score”.

Lo and behold, the Big 4 Score is more correlative with NFL success than any individual metric on its own, even the already-strong college PFF grade. There was a correlation coefficient of .624 between Big 4 Score and NFL PFF grade, which is eye-popping.

Take a look at how the group stacks up. The players are ranked from top-to-bottom by their Big 4 Score, with their NFL PFF grades beside them to showcase the correlation. Shown on the right are the four college metrics that factor into the Big 4 Score.

The scatter plot helps us visualize the correlation.

What does it all mean?

It goes to show a very simple truth: When it comes to scouting edge rushers, you should probably ignore “traits” and “projection”, and just focus on the simple question: “Is this guy productive?”

There are countless variables involved in quarterback play that muddy up the scouting process. What scheme is he in? How difficult are the throws he is being asked to make? How many progressions is he being asked to go through? How much is he being asked to handle at the line of scrimmage? Can his receivers run routes? Can they catch? Can his line protect? Does he have a run game? Are his coaches using his skill set to the best of his ability?

When it comes to edge rushers (and defensive linemen in general), these types of questions don’t exist to nearly the same degree. A college prospect’s job and circumstances are not going to change too much in the NFL. Some might slide to a different spot on the line or play with slightly different techniques as they move into a different scheme, but at the end of the day, the job is the same: beat the blocker in front of you.

If you’re good at it in college, you will likely be good at it in the NFL. If you’re not very good at it in college, you likely won’t be in the NFL.

There are many exceptions, of course, but generally speaking, college production is a strong indicator of how well a first-round prospect will perform in the NFL. More or less, most edge rushers have the same job, which means the primary thing that can change a player’s production in the future is their own individual skill development (rather than improvement or regression based on their environment).

The same cannot be said for quarterbacks. Every quarterback is asked to handle a significantly different job than the one on the opposite sideline, and for that reason, the final results on the stat sheet are essentially meaningless as tools for projection. A quarterback’s production and success can alter drastically depending on their environment. It is an apples-to-oranges comparison to stack quarterbacks against other quarterbacks; nay, an apples-to-asparagus comparison.

For edge rushers, though, it’s essentially apples-to-apples. To get technical, maybe it’s Gala-to-Honeycrisp, but you get the point: an edge rusher’s job is stable, consistent, and predictable, which makes production metrics more meaningful as a tool for projection.

At quarterback, the most correlative metrics were based on tendencies (deep pass attempt rate, scramble rate) rather than production (overall PFF grade, adjusted completion percentage). It shows that we should be scouting quarterbacks based not on their performance, but on their underlying traits and habits, as these are the things they will take with them to any NFL environment and will be built upon in their development.

It would seem that we should take the opposite approach with edge rushers. We get to see hundreds upon hundreds of college reps in which edge rushers are asked to do the same thing: go get the quarterback. Unlike quarterbacks, we get to see all edge rushers across the country perform in essentially the same situations—over and over again. The more consistently they succeed over these large samples of stable, repeatable situations, the likelier it is that they will be able to thrive at the same job in the pros.

Many NFL teams make the mistake of drafting edge rushers in the first round based on their perceived “upside” despite a lack of first-round-worthy production. These teams fool themselves into thinking that a player with elite tools will eventually grow into an elite football player, when they should be looking at it the other way around.

If a player had an overwhelming physical advantage in college and still could not produce at a high level, how is he going to succeed when his athletic advantage shrinks significantly against world-class NFL athletes?

Lighting up the combine after failing to produce in college is more of a red flag than a green one. It suggests that the prospect simply does not know how to beat blockers. Once he gets to the league, those same physical traits that make scouts drool are going to mean a whole lot less than they did in school, when many of the linemen he faced will never play professionally.

In the NFL, even the worst talents were standouts in college. To consistently win pass-rush reps in the pros, you must be able to beat blockers with technique and skill. If you could not do it in college, there is a good chance you will not suddenly figure out how to do it against stronger competition, especially if you struggled to dominate despite a substantial physical advantage.

The other side of the coin is also true. Teams pass on productive prospects due to concerns like arm length or a slow 40 time, when they should really be focusing on the very simple question: “Is he winning?” If he figured out how to win in college, he’s probably got the chops to figure it out in the NFL, too. Being productive in college despite limited traits, especially compared to rival prospects with better traits, only further highlights how skilled the prospect is.

Nothing summarizes this phenomenon more than the Jacksonville Jaguars’ baffling decision to select Travon Walker over Aidan Hutchinson with the first overall pick in 2022.

Of the 48 prospects in the data sample we analyzed today, Walker’s college production is the worst by a large margin. The Georgia product was extremely underwhelming in all four of the key metrics we broke down. Walker did not collect sacks at a high rate, did not create pressure at a high rate, did not win his pass-rush reps at a high rate, and, even after accounting for his run defense, did not grade well as an overall defender at PFF.

You know who accomplished all of those things, though? Hutchinson.

The same Hutchinson with those T. rex arms (32⅛”).

Instead of taking the guy who proved he could play football, Jacksonville elected for the guy with longer arms (35½”) and a faster forty time (4.51), all just to pray that he could eventually learn how to play football as well as Hutchinson.

Surprise! Four years later, he hasn’t.

The Walker-Hutchinson blunder is the most obvious traits-over-production gaffe in recent NFL history, but as you scroll down the chart above, you will see plenty of workout warriors who broad-jumped their way into the first round despite clearly not being productive enough to warrant first-round conversation.

Joe Tryon-Shoyinka, Payton Turner, Myles Murphy, Vic Beasley, and Bud Dupree are just a few first-round picks with 9.00+ Relative Athletic Scores who got drafted based on their traits despite lowly production (relative to first-round picks, not relative to the average college player) in key metrics, and went on to bust in the NFL.

Moving forward, the Jets and other NFL teams can get a leg up in edge scouting by steering clear of workout warriors who did not produce at an elite level in college. The focus should be on identifying players with dominant performances across predictive metrics like overall PFF grade, sack rate, pressure rate, and pass-rush win rate.

If you stick to selecting edge rushers with elite-level college production in these four metrics, history says there is a good chance you will hit at a high rate.

Stay tuned for a follow-up article in which we evaluate how some of the top EDGE prospects in the 2026 draft class fared in some of these metrics.